The Cool Web: A Robert Graves Oratorio is a large-scale choral work for baritone, SATB choir, children’s voices, and chamber orchestra, written to commemorate the centenary of the First World War.

This thrilling and deeply moving work by Bath-based composer Jools Scott and librettist Sue Curtis uses the poems Robert Graves wrote as a young soldier to trace his journey from the peace of an English school to the Somme and back.

Music and libretto combine to chart the tension between words and experience—the journey from innocence through anticipation, camaraderie, incoherent horror and madness, to the final resolution and an attempt to find peace through poetry. The subject matter is intensely challenging but as powerful now, and as relevant to humanity, as it was over a century ago.

Listen to the Complete Work

Recording from the Flanders Remembers concert at St Paul’s Cathedral, 2018

Three Woods, Three Worlds

At the heart of The Cool Web lies a powerful motif: the wood. Sue Curtis, in compiling the libretto, wove together Graves’s poetry to create a journey through three very different woods—each representing a distinct phase of the soldier’s experience.

The English Wood

The oratorio opens in the tranquil English wood—the land the soldiers were fighting for. In Graves’s poem An English Wood, we find a place of gentle beauty and safety:

Here nothing is that harms—

No bulls with lungs of brass,

No toothed or spiny grass…

Only, the lawns are soft,

The tree-stems, grave and old;

Slow branches sway aloft,

The evening air comes cold,

The sunset scatters gold.

This is England as sanctuary, as home—green fields where small pathways “idly tend towards no fearful end.”

The Haunted Wood

But as the oratorio progresses, the wood transforms. In Outlaws, the birds of Allie give way to something far more sinister:

Owls: they whinny down the night,

Bats go zigzag by.

Ambushed in shadow out of sight

The outlaws lie.

Old gods, shrunk to shadows, there

In the wet woods they lurk,

Greedy of human stuff to snare

In webs of murk.

The old gods awaken, hungry for sacrifice. The safe, sheltering wood darkens into something ancient and terrible—a preparation for what is to come.

Mametz Wood

The final wood is the most devastating. Mametz Wood, on the Somme, where the 38th Welsh Division suffered terrible casualties in July 1916, and where Graves himself served and was wounded so severely he was reported dead. It was here, collecting greatcoats from dead Germans for his freezing men, that he encountered the corpse that inspired his poem A Dead Boche—written, as he said, “as a way of putting people off war.”

Graves later described returning to Mametz after the battle: “It was full of dead Prussian Guards, big men, and dead Royal Welch Fusiliers and South Wales Borderers, little men. Not a single tree in the wood remained unbroken.”

The transformation is complete: from the soft lawns and sunset gold of England to the blackened stumps laden with bodies that the old gods thirsted for.

Goliath and David

One of the most powerful movements in the oratorio is Goliath and David—a devastating inversion of the biblical story. In Graves’s retelling, David loses. The poem was dedicated “For D.C.T., Killed at Fricourt, March 1916″—David Cuthbert Thomas, only twenty years old, a friend beloved by both Graves and Siegfried Sassoon.

David had been hit in the throat but walked to the dressing station; they thought he was safe. Then he unexpectedly choked and died in front of a doctor who could not save him. Sassoon went mad with grief. This poem was Graves’s response:

Steel crosses wood, a flash, and oh!

Shame for beauty’s overthrow!

(God’s eyes are dim, His ears are shut.)

One cruel backhand sabre-cut—

“I’m hit! I’m killed!” young David cries,

Throws blindly forward, chokes… and dies.

And look, spike-helmeted, grey, grim,

Goliath straddles over him.

The poem marks the end of belief—that courage and beauty could prevail against superior firepower, that human spirit could defeat the machine. As Sue Curtis wrote in her programme notes: “Beautiful young warriors died as easily as weak cowards; human beings themselves finally defeated by the machine.”

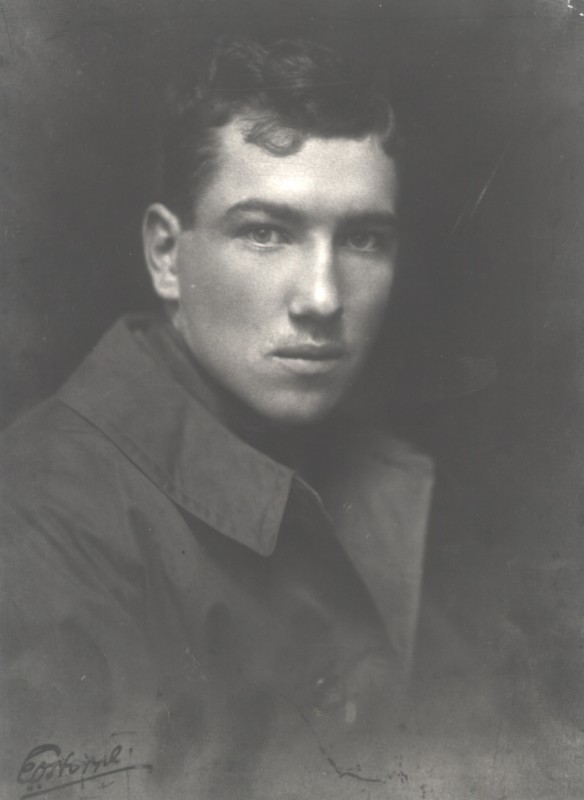

Robert Graves: The Poet-Soldier

Graves was just nineteen when he arrived on the Somme—the memories of childhood not far behind him. He served with the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, where he met and befriended fellow poet Siegfried Sassoon. On 20 July 1916, near High Wood, a German shell exploded close to Graves, piercing his chest with shrapnel.

He was taken to a dressing station near Mametz Wood, where it was expected he would die. A letter was sent to his family stating he had died of his wounds; his death was announced in The Times. Only when he was found still breathing while being carried to burial was he sent to hospital. His parents received news of his death one day after receiving a letter from Graves himself saying he was recovering.

Though he survived, shell shock haunted him for years. As he wrote in Goodbye to All That: “Since 1916, the fear of gas obsessed me: any unusual smell, even a sudden strong smell of flowers in a garden, was enough to send me trembling.”

Performance History

It has been an extraordinary honour as a composer to hear The Cool Web performed by three different world-class ensembles, under two distinguished conductors, in some of Britain’s most magnificent venues.

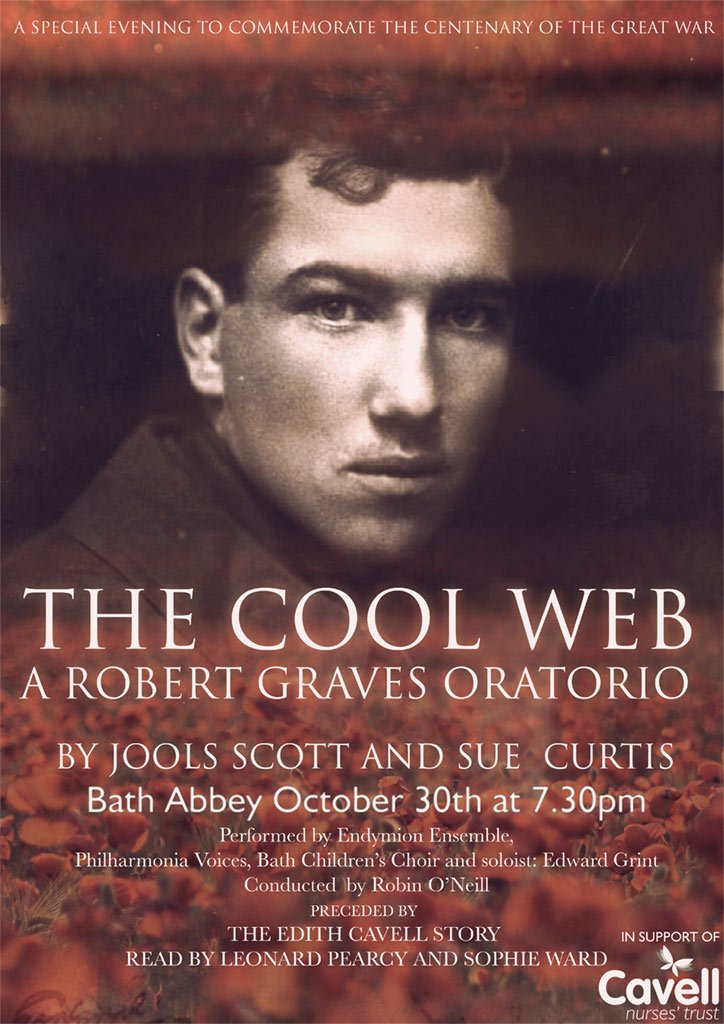

World Première – Bath Abbey

30 October 2014

Endymion Ensemble, Philharmonia Voices, Melody Makers of Bath Abbey

Conductor: Robin O’Neill

Baritone: Edward Grint

The première took place in Bath Abbey to mark the centenary of the Great War. The performance received a spontaneous standing ovation, with one reviewer declaring: “There has been a lot of magnificent English choral music written in recent years – the work of James MacMillan and the late John Tavener spring to mind – and I believe Jools Scott’s work is in keeping with the very best of this.”

Wimbledon International Music Festival

November 2017

Philharmonia Orchestra, Sonoro Choir

Conductor: Robin O’Neill

The Cool Web opened the prestigious Wimbledon International Music Festival, with 20,000 Merton primary school children participating in related educational events across 54 schools—learning and singing First World War marching songs before marching from school to school offering poppies.

St Paul’s Cathedral – Flanders Remembers

8 November 2018

Flanders Symphony Orchestra, St Paul’s Cathedral Choir & Consort, St Paul’s Cathedral Choristers

Conductor: Dirk Brossé

Baritone: Edward Grint

The closing concert of the official UK and Belgian centenary programme for 1914-1918. Flemish minister-president Geert Bourgeois greeted some 2,000 guests. The audience included members of the British parliament, the lord mayors of London and Westminster, dignitaries of the Queen, EU ambassadors, and veterans.

I was a chorister at St Paul’s Cathedral from the ages of 8 to 13—this is where I started composing, where I was first exposed to the wonderful English choral repertoire. Having The Cool Web performed there was the highest of accolades. The concert was the greatest moment of my life.

At the end of the performance, poppies fell from the Whispering Gallery, drifting down through the vast dome onto the performers and audience below. I hope Robert Graves would have been proud.

It was a particular honour that William Graves, Robert’s son, was in the audience, alongside other members of the Graves family.

Video: Sue Curtis and Jools Scott discuss The Cool Web

A Review of the World Première

THE Cool Web, created to commemorate the centenary of the Great War, had its triumphant première on Thursday 30th October, when baritone Edward Grint was joined by the Philharmonia Voices, the Melody Makers of Bath Abbey (a children’s choir from local schools) and the Endymion Ensemble under the distinguished baton of Robin O’Neill.

To say that it was a privilege to have been there is such an understatement; the performance was one of the most profound and moving tributes to the fallen I have encountered in a year when there have been so many. Scott’s beautiful, lyrical, energetic music was both glorious and deeply disturbing and conveyed the richness of Robert Graves’ poetry with an unfailing passion and intensity.

There is so much to admire in Scott’s music. It is totally accessible – the enthusiastic audience loved it – but it avoids saccharine sweetness, it is varied in style – reminiscent of Vaughan Williams and Britten at times – yet has a definite voice of its own. His instrumental writing is rich and full of colour, sometimes charming, sometimes menacing, whilst his choral writing is simply sublime.

The soaring soprano lines in particular were breathtaking… whilst the children’s rendition of Allie was utterly delightful and one of the highlights of the evening.

Most of the solo work was in the very capable hands of British baritone Edward Grint whose commanding performance was absolutely central to the success of the work. He became Robert Graves for the duration, his thrilling voice and facial expressions capturing the emotion of the piece with intensity and sincerity. We hung onto his every word in Goliath and David, A Child’s Nightmare was utterly chilling whilst The Last Days of Leave – an a cappella piece for soloist and male voice quartet – was heartbreakingly lovely.

I sincerely hope that The Cool Web finds a place in the established repertoire… there has been a lot of magnificent English choral music written in recent years – the work James MacMillan and the late John Tavener spring to mind – and I believe Jools Scott’s work is in keeping with the very best of this. His is a name we will be hearing a lot of in the future and the spontaneous standing ovation was richly deserved.

Read the full review here.

The Title Poem

The oratorio takes its name from Graves’s poem about how we use language to distance ourselves from overwhelming experience—to “spell away the soldiers and the fright”:

Children are dumb to say how hot the day is,

How hot the scent is of the summer rose,

How dreadful the black wastes of evening sky,

How dreadful the tall soldiers drumming by.

But we have speech, to chill the angry day,

And speech, to dull the rose’s cruel scent.

We spell away the overhanging night,

We spell away the soldiers and the fright.

There’s a cool web of language winds us in,

Retreat from too much joy or too much fear…

The journey of the oratorio follows this arc: from the vivid, unfiltered responses of youth to the wariness of experience, and back—through war, shell shock, and healing—to an attempt at peace through poetry.

Goodbye to All That

Robert Graves’s memoir Goodbye to All That remains one of the definitive accounts of the First World War. If you’re moved by The Cool Web, I strongly encourage you to read it.

I hope he would have been proud of what Sue and I created together. The poetry he wrote as a young man—immediate, passionate, heartbreaking—gave us everything we needed. We simply tried to honour it.

Further Listening

SoundCloud Excerpts from Bath Abbey Première

Credits

Music: Jools Scott

Libretto: Sue Curtis (compiled from the poetry of Robert Graves)

Poetry: Robert Graves, by kind permission of the Robert Graves estate

With grateful thanks to William Graves and the Graves family for their support of this project.